Understand your truck’s powertrain and improve fuel economy: Driver’s Education

Truck engines are designed with an operating range in mind, a band of engine rpm where they operate at peak fuel efficiency for the work they’re doing. That “sweet spot” varies across different makes and models. A Detroit DD15 will be slightly different from a Cummins X15; a Paccar MX 13 will differ from a Volvo D13.

Regardless of the engine make or model, the biggest impact on the engine’s efficiency comes from the choice of geartrain and highway cruising speed.

Before digging into gear ratios and tire sizes, we need to understand the relationship between engine speed, engine torque, and engine horsepower, and how they affect fuel economy. Engines sip less fuel at lower engine speeds (rpm) than higher speeds. Keeping engine rpms down will lower your fuel bill. The object is to keep average engine revs per mile low.

Truck makers complete a bunch of calculations before approving a powertrain spec’. They look at the intended application, gross vehicle weight, anticipated cruising speed, gradeability, startability, and more. They already know what the engine’s performance curves look like. The next step is determining the correct transmission and drive-axle gear ratios (and tire size) to match the powertrain spec’ to the intended application.

Once the truck is built, making changes to the spec’ is difficult and expensive.

Torque and horsepower charts

When spec’ing an over-the-road truck, there are tons of drive axle gear ratios and transmission output ratios to consider.

Starting with the transmission, we have direct drive (1:1) and usually two overdrive options. Direct drive means the output shaft turns one full turn for every full turn of the input shaft. Direct is said to be the most efficient because torque flows through the fewest number of gear meshes, minimizing losses to friction.

There are two typical overdrive ratios — 0.87:1 (single overdrive) and 0.73:1 (double overdrive). Some manufacturers offer a single ratio somewhere in the middle. In practical terms, overdrive means the output shaft respectfully turns 1.13 and 1.27 times for every one turn of the input shaft. In other words, the transmission output shaft is turning faster than the engine crankshaft. Some say overdrive is less efficient than direct drive because additional gear meshes are required, but they concede frictional losses are small.

There’s more choice with drive axle gear ratios. Actually dozens, depending on the intended application, from mountain-climbing off-road trucks to fuel-sipping highway trucks. The higher the ratio (say, 4.11:1), the more performance you’ll see, because these ratios allow the engine to run on the high side of the rpm range where higher horsepower lives. The lower the ratio (like 2.64:1), the better fuel efficiency will be because the engine is turning at a lower speed.

Engine manufacturers publish torque and horsepower charts for their engines. These help spec’ the truck while providing valuable clues for drivers on how best to operate the engine. If you operate a truck with an automated transmission, the engine and the transmission are programmed to work together to optimize fuel economy or performance (usually the buyer’s choice). It’s particularly important for drivers who have manual transmissions, and a greater choice of gears, to understand these charts.

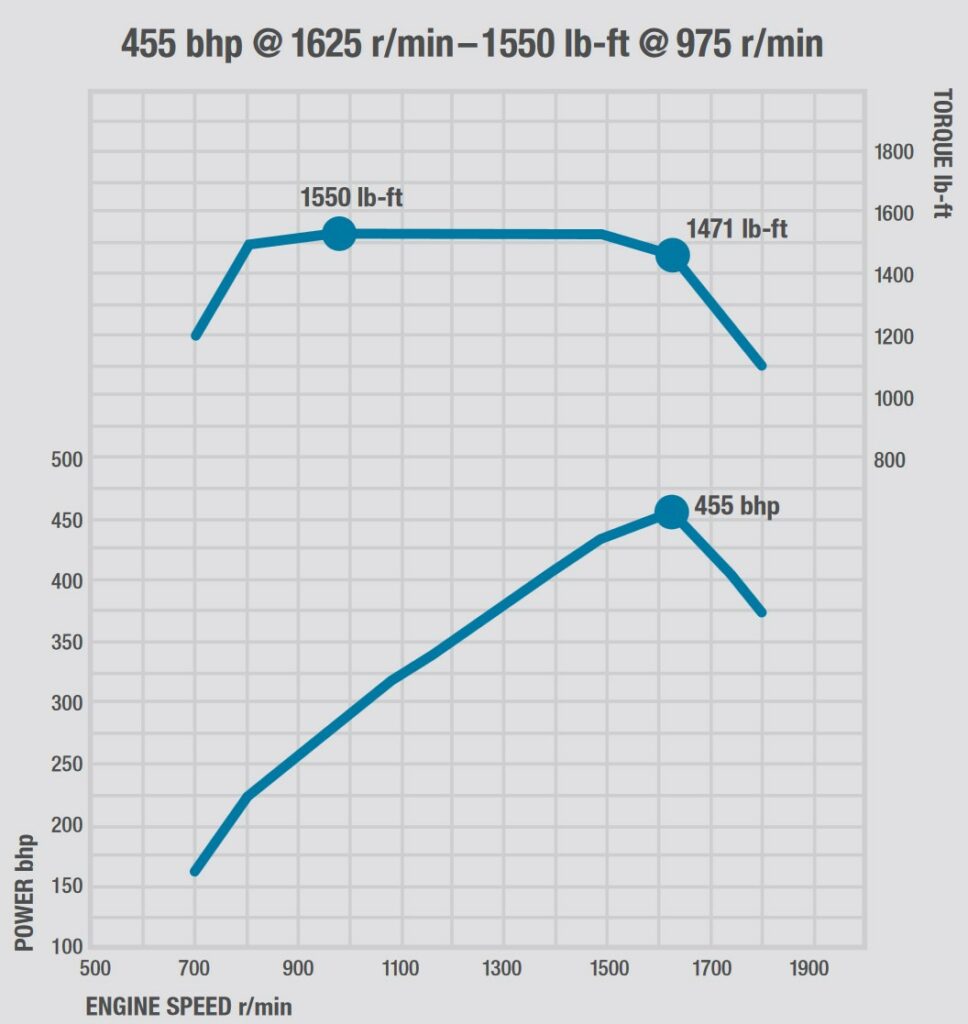

The chart below represents a 2021 Detroit DD15 engine, rated at 455 hp and 1,550 lb-ft of torque. I chose this chart to illustrate the discussion only because it’s clean and easy to read. Torque and horsepower charts for other makes and models look a little different, but they convey the same information.

Here’s what we can glean from this chart:

- The peak torque (top line) of 1,550 lb-ft extends across a range of 975-1,500 rpm

- peak horsepower is produced at 1,625 rpm (torque at that point is 1,471 lb-ft)

- if you wanted peak fuel efficiency from this engine, you’d gear it to cruise somewhere between 1,100-1,200 rpm

- if you wanted peak performance from the engine (higher cruise speed, heavier loads, more hills), you’d gear it to cruise at 1,300-1,500 rpm

It’s worth noting that, back in the 1980s and ‘90s, engine torque curves had distinct humps where peak torque was available in a very narrow rpm band found fairly high in the rpm range. Torque output dropped dramatically below that point and tapered off above that point, though not quite as sharply.

Electronic engine controls made possible flatter and broader torque plateaus, rather than humps. This increased drivability and allowed drivers to stay in top gear longer. Around 2004-‘07, it was common to see torque curves plateau between 1,100 and 1,400 rpm, giving drivers a 300-rpm band of highly useable torque. Today, the peak torque plateaus can extend from 900-1,500 rpm, giving drivers the equivalent of a full gear’s worth of peak torque.

This has really changed the thinking on how powertrains are spec’d. However, some drivers who learned to drive on older engines haven’t yet adapted to the newer torque ranges and still spec’ and drive their trucks according to outmoded thinking.

Some of the following statements won’t directly apply to older trucks, but the principles are the same.

Gear fast, run slow

The concept of gear fast and run slow has been around for years, but in 2011 Volvo Trucks christened it “downspeeding” and began marketing what it called an XE powertrain (for extra efficiency). It boasted an engine speed of 1,150 rpm at 65 mph using a D13 engine with 425 horsepower and 1,750 lb-ft of torque, an I-Shift overdrive transmission with a 0.78:1 ratio, and rear axle ratios of 2.64:1.

When introduced, Volvo claimed a 1.5% boost in fuel efficiency for every 100 rpm drop in engine speed compared to non-XE configurations. A 200-rpm drop saved 3% in fuel.

Volvo didn’t invent the concept, but was first to market with a drivetrain that would not have been possible with a manual transmission. The proprietary software allowed the engine and the transmission to communicate, which ensured the engine stayed as close as possible to the ideal engine speed range. While drivers could do that with a manual transmission, too, it would demand a huge share of a driver’s attention.

Downspeeding — or gear fast and run slow — still works as a concept with manual transmissions. It’s just impractical to go as low as you might with an automated transmission. This is where it pays to check your engine’s performance curves – not just for spec’ing, but for deciding how to drive it well. Once you let the engine drift down to the lower end of the peak torque band you’ll have to downshift. If it goes too low, you might need to grab a lower gear, or maybe even two.

As noted above, current-generation engines have wide peak-torque plateaus, with a 400-500 rpm range in some cases. Older engines may have only 200-300 rpm to play with. If you’re geared too close to peak torque for a particular road speed, you’ll have nothing in reserve when you hit a grade or push a headwind. And the heavier you are, the more inadequate your engine will feel because the revs are going to fall off even faster. Driveability is gone because top-gear gradeability has been compromised.

The result is you’ll probably want to run a gear down, or at least split the top gear with a multi-speed transmission. That, however, will increase your average engine revs per mile and your fuel consumption.

Matching engine speed and road speed

Owner-operators looking for fuel economy through a gear-fast and run-slow strategy can run into problems when the work strays from the spec’.

For example, if you spec’ the truck to cruise at 70 mph (112 km/h) at 1,200 rpm on nice flat highways, you may be cruising at 1,100 rpm at 65 mph (104 km/h). In some cases, that would take you closer to the peak-torque drop-off point, and possibly force more downshifts. If you’re running into headwinds or in hilly terrain, you’ll be downshifting constantly, and the truck will soon become pretty annoying to drive.

For owner-operators, predicting where they’ll be working from one year to the next or what sort of terrain or load they will be pulling can make precise spec’ing decisions difficult. In other words, spec’ing a truck for a certain application may be fine this year, but that spec’ might not be so fine after changing jobs.

The same thinking applies to owner-operators buying used equipment. There’s no point buying a long-legged western highway truck to run the U.S. eastern seaboard.

This exact point created problems for some truck owners when speed limiters were imposed in Ontario and Quebec in 2008. Trucks geared to run at 70 mph but limited to 65 mph may have had to run a gear down to maintain drivability. At 75 mph – a speed limit seen in some western states — a truck spec’d to run at 65 mph will be running at a much higher engine speed than originally intended. Fuel economy suffers whether too fast or too slow.

Spec’ your truck properly from the get-go, and then drive it the way you spec’d it.

A good truck dealer will be able to walk you through this process using the exact specification for the truck you’re building, and can help you spec’ the truck for the application you have in mind. You obligation at this point is being honest about what you plan to do with the truck.

And when buying a used truck, it’s in your best interest to do some of these calculations yourself to ensure you get the right powertrain for the job.

Have your say

This is a moderated forum. Comments will no longer be published unless they are accompanied by a first and last name and a verifiable email address. (Today's Trucking will not publish or share the email address.) Profane language and content deemed to be libelous, racist, or threatening in nature will not be published under any circumstances.

A great article from Jim as usual. I read his work and this Magazine since 1998. I run a small fleet for FedEx Ground here in Woodbridge.ON. since 2015 and owned trucks since 2007, have been driving since 1997. I prefer to get involved with doing my own specifications with all my New truck orders. Since we do not pull heavy, I prefer to go always with a big capacity 15L engine , with at least 505 horses and a minimum of 1800 lb/ft Torque if I can get it,

( these days fortunately we can ) and a very fast rear end Diff. ratio. The fuel economy numbers are very good for my application, pulling two 28′ pup trailers ( you get some drag between them pups) , I usually get an average ( year round) of 32 lts/100 kms ( or a little less) for all my 6 units. For example at 105 km/hr my 2022 Peterbilt 569 with a Cummins X15, 505 horses and 1800 lb torque with a 2.85 ratio in the back , automated tranny. , doing Woodbridge to Ottawa , is turning at around 1170 rpm, and getting about 31.7 lts/100 kms average in the winter. I ordered back then my 2020 Kenworth T680 , Cummins X15, 13 speed manual with 3.01 Ratio also doing great on fuel. I am receiving two more new Freightliner Cascadias soon, I went really aggressive on one of them, ( it is an experiment, I hope not an expensive one), DD16 engine, automated, 2.58 Ratio and the other one ( a Spec. already proven on the 2022 Pete.) , Cummins X15, automated, 2.85 Ratio. We do only Ontario at the moment , so mostly all units are running on flat land most of the time, 600 kms up to 900 kms a night, nothing too crazy for Regional Trucking. The problem I personally see over the years with Owner-Ops, is that a lot of them are NOT mechanically inclined, they do not read trucking material, they go with advice from friends , and therefore make big equipment mistakes. Also is worth noting, things change a lot every few years, I talk to people in the industry, and they are still stuck in the past, gone are the days that you had to downshift at 1200 rpm. Also lastly I have to mention that most New drivers these days, do not really want just to drive the truck because it is smth. they love to do. Most of them are in it just to make money and there is for the most part no love or feeling for the profession of driving.