What role will Canada play in the burgeoning global hydrogen economy?

The federal government has announced ambitious plans to develop a hydrogen economy in Canada and if it’s to be successful, trucking could play a large role in both its development and as a consumer.

In December, the feds released Hydrogen Strategy for Canada, a 141-page manifesto outlining opportunities to become a dominant player in the emerging global hydrogen economy. Canada is already among the top 10 hydrogen producers in the world and is home to Ballard Power Systems, a global fuel cell provider.

The Alberta Zero Emissions Truck Electrification Collaboration (AZETEC) program will put two hydrogen-fueled trucks on the road later this year, testing the technology in real-world applications pulling 63,500-kg gross weights with Trimac and Bison Transport. Deployment of the trucks was to have commenced last year, but the Covid-19 pandemic delayed the project.

And Quebec is about to be home to the largest hydrogen-producing proton exchange membrane electrolyzer in the world. But at the same time there are hurdles to overcome, including a growing aversion to pipelines, a lack of market-ready vehicles, and an inexpensive, efficient and familiar competitor – diesel.

‘Virtual’ pipelines

Even if trucking is slow to develop as a hydrogen consumer, there is already increasing interest for it as a clean energy source in other applications. And trucks will play a vital role in transporting hydrogen from where it’s produced, to where it’s needed. Recently, Quantum Fuel Systems announced a deal to supply Canadian natural gas supplier Certarus with North America’s first Type 4 virtual pipeline tank trailers for hydrogen transportation.

A Type 4 vessel is constructed of carbon fiber, with an inner liner of polyamide or polyethlene plastic for high strength and low weight. The tank is housed within a plain-looking 40-ft. overseas shipping container.

The trailer has already been approved for hydrogen transport by Transport Canada and the U.S. Department of Transportation, and though it has been modified for the specific molecular composition of hydrogen, “It’s going to look identical to what we have in the field today,” Steve Tolke, vice-president, virtual pipeline with Quantum Fuel Systems told Today’s Trucking.

So far, interest in the trailers is mostly coming from fleets that are already in the business of transporting natural gas and see the potential emergence of hydrogen as a new opportunity.

“Most of our customers are just like Certarus – they move gas for a living,” Tolke said. “We’re getting a lot of calls from existing customers.”

Quantum’s largest trailer can carry about 1,200 kgs of hydrogen. For some perspective, while Nikola no longer reveals the planned capacity for its hydrogen tanks, the company previously disclosed an 80-kg tank could provide about 700 miles (1,120 km) of range. A 1,200-kg trailer shipment therefore could fuel 15 fuel cell electric trucks equipped with 80-kg tanks.

Over-the-road hydrogen transport will require production to be close to consumption to keep costs down. Or, hydrogen can be sent by pipeline, but that comes with challenges of its own. Bruce Winchester, executive director of the Canadian Natural Gas Vehicle Alliance (CNGVA), told Today’s Trucking that hydrogen can travel via existing natural gas pipelines and be extracted at its destination. But that’s not ideal, because of the expense of extraction.

“If it goes to scale, we probably will see pipelines and we may see it co-mingled with natural gas,” he said.

Initially, however, he agreed bulk trucking will be the most commonly used mode of transport. But as the hydrogen economy scales up, one energy expert says pipelines will be needed.

“We got to get over this friggin’ pipeline thing,” Maggie Hanna, a fellow at the Energy Futures Lab, recently said in an interview with the CBC, regarding growing opposition to pipelines. “It is the number one safest way to move any fluid.”

Similarities to natural gas

Hydrogen can be transported via natural gas pipeline (at up to a 20% blend) or using similar tanker trailers over the road, and the similarities don’t end there. That’s why the CNGVA is getting involved in discussions about the emerging fuel, which some might consider a competitor to natural gas.

“I believe a lot of our member companies on the supply side are going to supply hydrogen for this market when it’s ready and when fleets are interested,” Winchester said. He wants to see existing safety policies and procedures already used by the natural gas industry updated to accommodate hydrogen rather than writing them from scratch.

And he thinks fleets interested in transitioning to hydrogen fuel cells should first gain some experience with natural gas.

“A fleet will have a much easier time getting into hydrogen as a fuel if they spent some time or have some experience with natural gas,” he said. “Not all the equipment is interchangeable but a lot of it is.”

The talk about hydrogen as a fuel source reminds Winchester of where natural gas was about a decade ago, but that doesn’t mean it will be 10 years before fuel cells become viable.

“I’m not sure how quickly hydrogen is going to evolve as a fuel, but I know they have to step through a few hoops in the next one to five years,” he said.

One is cost – that of the equipment, and the fuel itself.

The Hydrogen rainbow

Hydra Energy is a B.C.-based “hydrogen-as-a-service” company built to serve commercial fleets. It recently inked a deal with Chemtrade to capture hydrogen emitted by a B.C. chemical plant for use as fuel by trucks fitted with Hydra’s hydrogen injection co-combustion system.

Badr Abduljawad, co-founder and director of operations with Hydra, told Today’s Trucking that it will able to offer customers hydrogen fuel at 5% less cost than diesel. But fuel cell trucks will require a purer hydrogen, so operators of those vehicles can be expected to pay more.

Hydra’s hybrid retrofit system reduces diesel consumption by about 40%, Abduljawad said, and he envisions over the next 10 years being able to completely wean the internal combustion engine off diesel without using expensive fuel cells.

“Hydrogen fuel cells are, as it stands today, extremely expensive to manufacture and unless the cost of manufacturing goes down it will be difficult for it to be competitive with internal combustion,” he said.

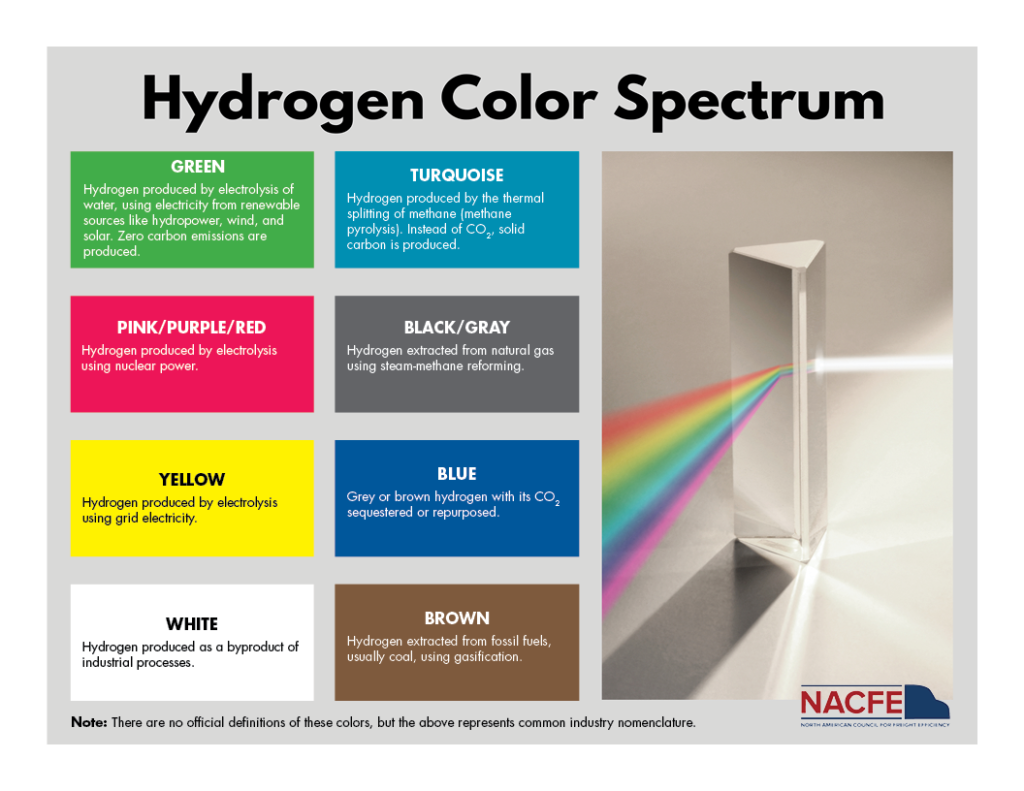

The hydrogen Hydra pulls from Chemtrade’s facility will be ‘green’ hydrogen – the most environmentally-friendly form, since any carbon emissions are already accounted for by Chemtrade. While there’s no standard definition for the various types of hydrogen, green hydrogen is considered the cleanest, as it contributes no carbon emissions.

Grey hydrogen is produced when the carbon emissions are allowed to escape into the environment, while blue hydrogen produces carbon, which is then captured and eliminated (burying it into the ground is one common method). Most hydrogen is produced from natural gas using a method call steam methane reform (SMR).

Electrolysis – breaking up water cells into oxygen and hydrogen – is another method of creating hydrogen, and this too can be green if the source of the electricity is carbon-free (ie. solar or wind-generated). The North American Council for Freight Efficiency (NACFE) takes the color spectrum further, differentiating between turquoise, red, yellow and white hydrogen, depending on production methods. NACFE would consider Hydra’s hydrogen to be ‘white’ as it’s produced as a byproduct of industrial processes. The industry is working to bring some official uniformity to the various definitions.

Hydra, for its part, is looking to partner with other chemical plants across Canada to create hydrogen, which can then be trucked to local fleets running trucks with its hydrogen retrofit systems.

“We find it to be most economical if the hydrogen production is within a 100-km radius [of consumption],” Abduljawad said.

Where are the trucks?

FCEVs themselves are still entrenched in the research and development stage. Nikola Motor Company, which was among the first OEMs to get tongues wagging over hydrogen-fueled heavy trucks, recently announced its first FCEVs will enter production in the second half of 2023, while its longhaul variant will be launched a year later.

It has partnered with U.S. brewer Anheuser Bush to develop the technology and will source its fuel cells from General Motors and Bosch.

Kenworth has built five T680 FCEVs in partnership with Toyota, with five more set to enter service this year. Those trucks are working at the Port of Los Angeles, and one made headlines as the first FCEV to summit Pikes Peak in Colorado. Hino has also partnered with parent company Toyota on a Class 8 hydrogen fuel cell tractor for the North American market, the first prototype of which is set to be built early this year.

Meanwhile, the race to be among the first to bring hydrogen fuel cell trucks to market has resulted in some strange bedfellows. Daimler and Volvo recently announced a global joint venture to develop hydrogen fuel cells, with initial production based out of Burnaby, B.C. The deal was approved and completed on March 1, with the new venture named cellcentric.

Cummins is also looking to lead the emerging industry. It has announced plans to work with Navistar on development of a Class 8 truck that Werner Enterprises will operate during trials in California. Cummins says it has more than 2,000 fuel cell installations already deployed globally and that it is building electrolyzers to generate green hydrogen. The largest of these is nearly complete – a 20-megawatt electrolyzer system in Becancour, Que. – which will be the largest in the world.

In addition to working with Cummins, Navistar is collaborating with GM to put a fuel cell truck into service with JB Hunt late next year.

While it’s not possible to purchase a Class 8 FCEV off the lot today, the technology is maturing in other segments, notes Kevin Otto, NACFE’s electrification technical lead.

“Hydrogen fuel cell heavy-duty trucks are technically viable,” he said. “The technology has been going through decades of maturation on buses, cars and industrial uses. Adapting fuel cells to heavy-duty trucks will invariably have a learning curve as all new technologies do, but fuel cells are much further along in production use and are not a brand new technology.”

Can Canada lead?

With plans in the works to bring hydrogen fuel cell trucks to market, and a commitment from government to develop a hydrogen economy, how realistic is it for Canada to become a major global player?

“What’s great about Canada is that we have an abundance of a lot of different energy types, and all the raw materials and technical know-how to produce significant amounts of hydrogen in Canada,” said the CNGVA’s Winchester.

But he noted it cannot be exported as easily as petroleum products or liquefied natural gas, so demand will have to be generated domestically or within North America. Even if low-cost hydrogen is produced here, will the demand materialize?

“I think it will be challenging to draw a lot of hydrogen vehicles into Canada and if we do, the price of diesel and natural gas is quite low in Canada,” he added. “The unfortunate problem we have in Canada is we have a lot of different energy sources chasing the same small number of energy consumers and we enjoy some of the lowest energy costs in the world.”

While the government may raise taxes on fossil fuels and incentivize cleaner alternatives, Winchester said there’s a limit to what that can achieve. And as it looks to kickstart the post-Covid economy, he said anything that increases transportation costs may get put on the back burner. But while he may be somewhat skeptical about trucking becoming a huge hydrogen consumer, he also sees other opportunities for hydrogen as a fuel, including rail and many stationary power applications.

“They may deploy somewhere else first, then adapt that technology to work on vehicles as those platforms move away from the current platforms we know to ones that have electric drive,” he said.

While there are obstacles to overcome, the feds are putting forth a serious effort to make the hydrogen economy a reality. They’ve committed $1.5 billion, and suggest their strategy will create up to 350,000 new jobs by 2050, when they expect to have a fueling network capable of supporting more than 5 million FCEVs.

“Hydrogen’s moment has come,” said Seamus O’Regan, Canada’s Minister of Natural Resources. “The economic and environmental opportunities for our workers and communities are real. There is global momentum, and Canada is harnessing it.”

Have your say

This is a moderated forum. Comments will no longer be published unless they are accompanied by a first and last name and a verifiable email address. (Today's Trucking will not publish or share the email address.) Profane language and content deemed to be libelous, racist, or threatening in nature will not be published under any circumstances.