Challenges remain in path for fuel cell electric trucks

TORONTO, Ont. – Hydrogen fuel cells have a future in trucking, but the pace of that future will have more to do with the creation and distribution of hydrogen than the evolution of the trucks themselves.

The observations emerge today from the North American Council for Freight Efficiency (NACFE) in its latest guidance report, part of a series of studies into fuel sources and fuel-saving equipment.

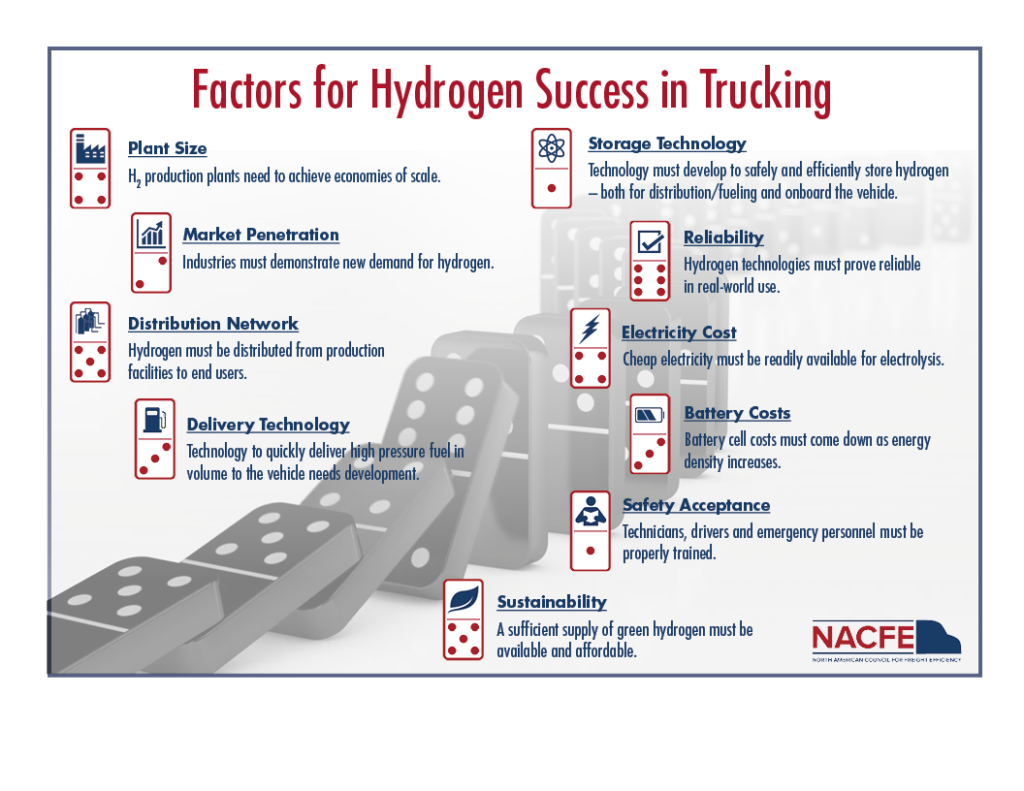

“The costs of hydrogen, vehicles, and hydrogen production all must come down significantly to make hydrogen economically competitive with alternatives,” Making Sense of Heavy-Duty Hydrogen Fuel concludes.

“Hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles are electric vehicles,” explains Mike Roeth, NACFE executive director. “It’s a range-extended electric vehicle.”

But rather than drawing electricity from a battery alone, the electricity comes from a fuel cell that’s powered by hydrogen.

A group known as the Hydrogen Council predicts 2.5% of trucks will adopt hydrogen as a fuel in 2030.

Fuel cell research

While any real quantities of fuel cell electric trucks are not expected in North America until 2023-25, there has been a series of related announcements around the world.

Hyundai has been responsible for one of the largest commercial rollouts so far, delivering seven Xcient Class 8 trucks in Switzerland, and setting targets to produce 2,000 vehicles for China, Europe and the U.S. in 2021.

Other initiatives have seen companies – even direct competitors – joining together in related research.

“These shared resources or collaborations that have been announced are a big deal when it comes to moving on … to the development and deployment,” Roeth said.

Daimler and Volvo formed a joint venture to develop, produce and commercialize fuel cell systems for heavy-duty trucks, including a system that will offer 300 kW of continuous power needed for longhaul trucks. Canada will be included in that work as one of two sources for the fuel cells themselves.

Upstart Nikola Motor says it will integrate GM’s Hydrotec fuel cell system into Class 7 and 8 commercial trucks, after failing to produce a system of its own, and is scheduled to test prototypes by the end of 2021. TransPower is testing a pair of International trucks powered by Hydrogenics fuel cells. Toyota and Kenworth have joined forces to test a pair of trucks and ports in Southern California.

California and Canadian emissions

The latter location plays a central role in much of the North American work.

California will require 40% of new trucks to be zero-emission vehicles by 2032, with all medium- and heavy-duty trucks to be zero-emission vehicles by 2045. Drayage applications are to make the transition by 2035.

But there is interest in Canada as well. The federal government has set a target of net-zero emissions by 2050, and is committing $1.5 billion to developing a hydrogen economy — establishing a refueling network to support more than 5 million fuel cell electric vehicles by 2050.

In the near term, the Alberta Zero Emissions Truck Electrification Collaboration (AZETEC) will see test trucks run by Bison Transport and Trimac Transportation from October 2021 to April 2023.

Evolving fuel cells

The idea of running vehicles on fuel cells isn’t exactly new. Fuel cells have been around for more than 70 years, powering buses in the last 20 years and cars over the last decade.

“Hydrogen fuel cell heavy-duty trucks are technically viable. The technology has been going through decades of maturation on buses, cars and industrial uses,” said Kevin Otto, NACFE’s electrification technical lead.

But that doesn’t guarantee a rollout without any challenges.

“The technology is both mature enough for truck manufacturers to begin production, but immature enough that its first owners should not expect problem-free use,” said Roeth. “Real-world fleet use for commercial freight is different, and there will be a learning curve.”

Pricing and scale

Given truck production volumes and target dates to build zero-emission vehicles, NACFE expects incentives, grants, credits and tax breaks to be part of the equation for “a while”.

“There are not enough heavy-duty trucks to create sufficient demand to scale up hydrogen production fast enough to accelerate cost reduction. Fleets adopting hydrogen might see high fuel costs for some years if trucks are the only incentive for hydrogen production,” Making Sense of Heavy-Duty Hydrogen Fuel says.

The scale needed to influence fuel prices will rely on broader applications at energy power plants, chemical companies, steelmakers, and other material producers, it adds.

Hydrogen – particularly cheap hydrogen – remains a regional solution.

Accepting compromises

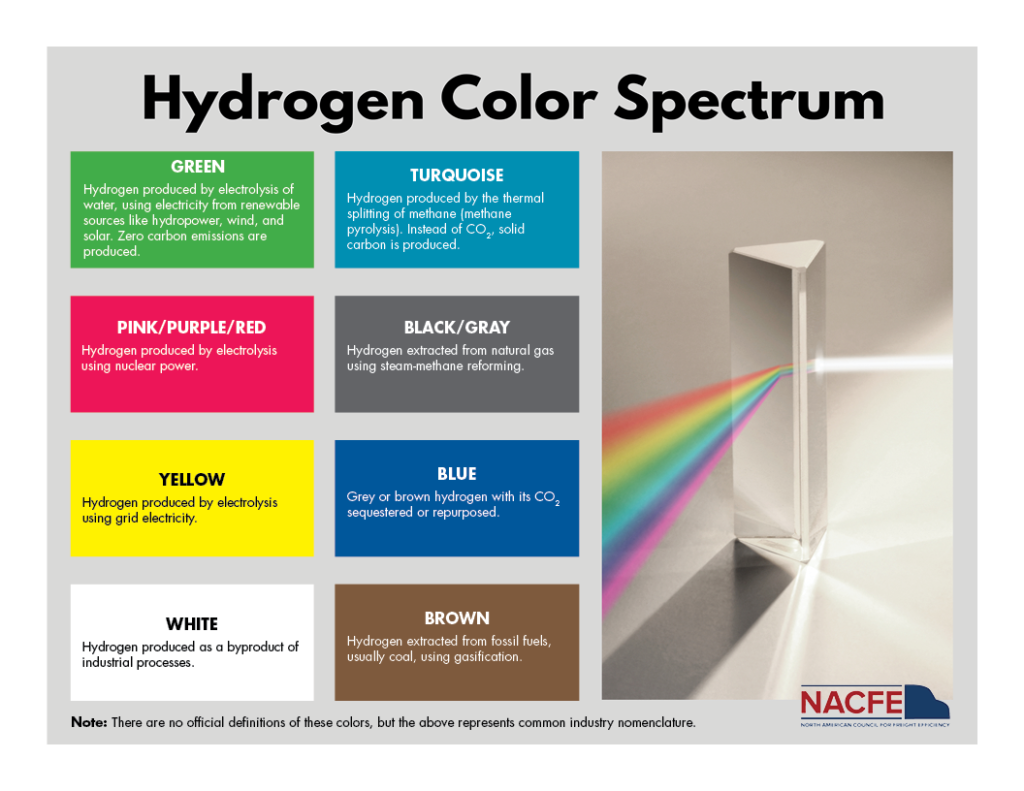

The council also stresses that purists pushing the goal of green hydrogen should accept that some compromises will be needed to allow for alternatives in the journey to zero emissions.

“Whether that electric future is battery-electric, fuel cell electric, or catenary wire electric, the key need is electricity,” the report notes. “The greenest method of producing hydrogen involves using electrolyzers powered by electricity, essentially running a fuel cell in reverse.”

More than 95% of the hydrogen produced today comes through steam method reformation at natural gas wells.

But hydrogen can be produced several ways. Electricity produced through a renewable energy source can create the fuel through electrolysis and water. Other options include using nuclear power or electricity from the grid, the byproducts of industrial processes, splitting methane, or applying a process known as gasification to fossil fuels.

There’s one factor that NACFE believes shouldn’t be part of the discussion, however.

“Stop comparisons of fill times,” it adds. “Fill times are moving targets for both fuel cell and battery-electric vehicles. In a zero-emission future world, as in California’s plans, diesel does not exist. What is the value of a comparison on fuel times?”

The most meaningful comparison for fuel cells is battery-electric vehicles.

“Hydrogen’s baseline competitor is not really diesel, but rather battery-electric vehicles. Heavy-duty battery-electric vehicles will share the market with hydrogen fuel cell ones as both are optimized best for different duty cycles,” Roeth said.

And the battery-electric vehicles likely have an edge.

“If an electric truck can do the job, you should buy an electric truck,” he said.

“It’s not like this thing is going to take off like a rocket. It’s going to be really slow,” Otto added.

Have your say

This is a moderated forum. Comments will no longer be published unless they are accompanied by a first and last name and a verifiable email address. (Today's Trucking will not publish or share the email address.) Profane language and content deemed to be libelous, racist, or threatening in nature will not be published under any circumstances.