NACFE breaks down idle-reduction options for fleets in latest report

A typical Class 8 truck spends six to eight hours a day idling, consuming about 0.8 gallons of diesel per hour, which adds up to one vehicle burning roughly 1,000–1,800 gallons of fuel annually, depending on climate, duty cycle, and operating practices.

This is according to the latest report from the North American Council for Freight Efficiency, released Dec. 18 as an update to NACFE’s original 2014 idle-reduction Confidence Report. The report examines how fleets can reduce idling without sacrificing driver comfort, safety, or operational efficiency. That can reduce fuel costs, which account for roughly 25% of a fleet’s total operating expenses. Avoiding excessive, unnecessary idling can save a fleet between $3,500 and $6,000 in fuel costs per truck each year, depending on current diesel prices

At an average diesel price of $4 per gallon, a single long-haul truck might waste $4,000 to $6,000 worth of fuel each year if it idles overnight, the report says.

Other that financial consequences, reducing idling can also help fleets achieve their sustainability goals, as each gallon of diesel burned emits approximately 22.4 pounds (10.1 kilograms) of carbon dioxide. This means excessive idling can generate up to 15 metric tonnes of CO₂ emissions per truck per year.

Wide range of technologies

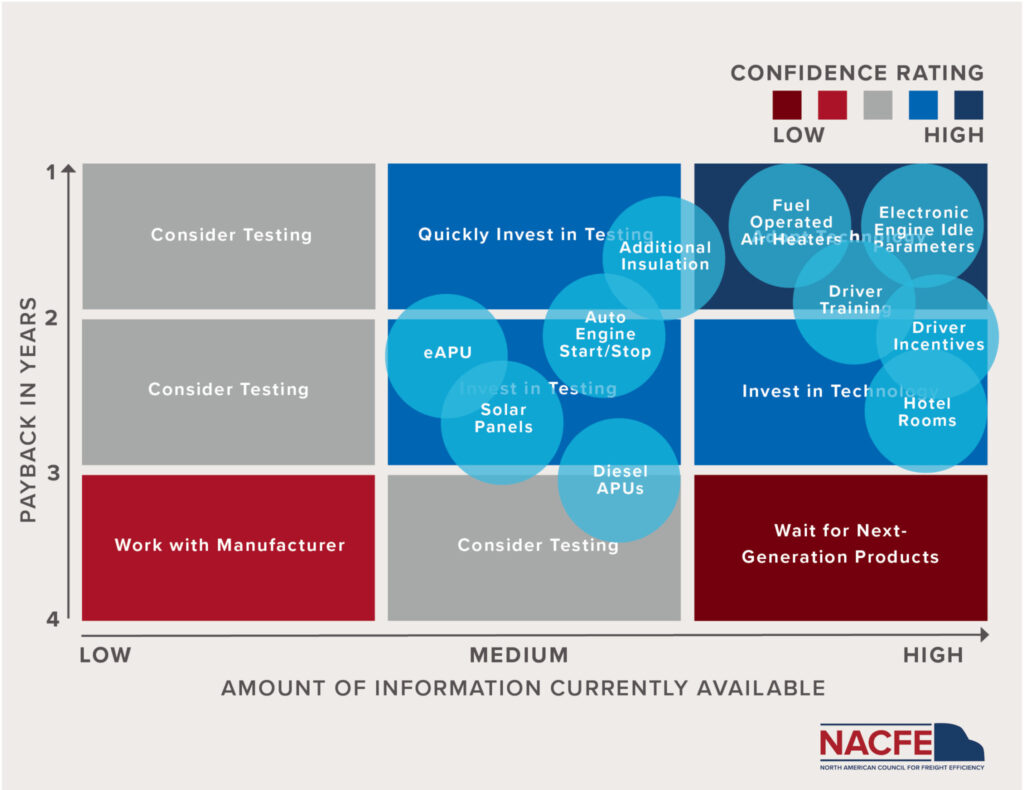

In its analysis, NACFE found that no single technology can be a silver bullet to solving the idling challenge, but the most effective idle-reduction strategies for fleets are those where they match technology to their specific duty cycles and combine them with ongoing monitoring, clear operational policies and driver training.

“Fleets should take a holistic approach to deploying idle reduction strategies,” said Dean Bushey, NACFE’s director of programs and lead author of the report, in a news release. “The most effective programs usually combine operational policies, driver engagement, and technology.”

The report evaluated a wide range of idle-reduction technologies, from diesel and electric auxiliary power units (APUs), fuel-operated air and coolant heaters, automatic engine stop/start systems to thermal management solutions, and off-board options such as truck stop electrification.

Fuel-operated heaters, for example, are among the most widely adopted idle reduction devices because due to its cost — typically ranging from $1,000 to $2,000 –and a quick payback in fuel savings. Compared to an idling engine, fuel-operated heaters can save a significant amount of fuel and lower emissions. One drawback is that they only provide heat; they do not provide cooling or AC power. They can also draw down the vehicle’s main batteries when in operation.

Diesel vs electric APUs

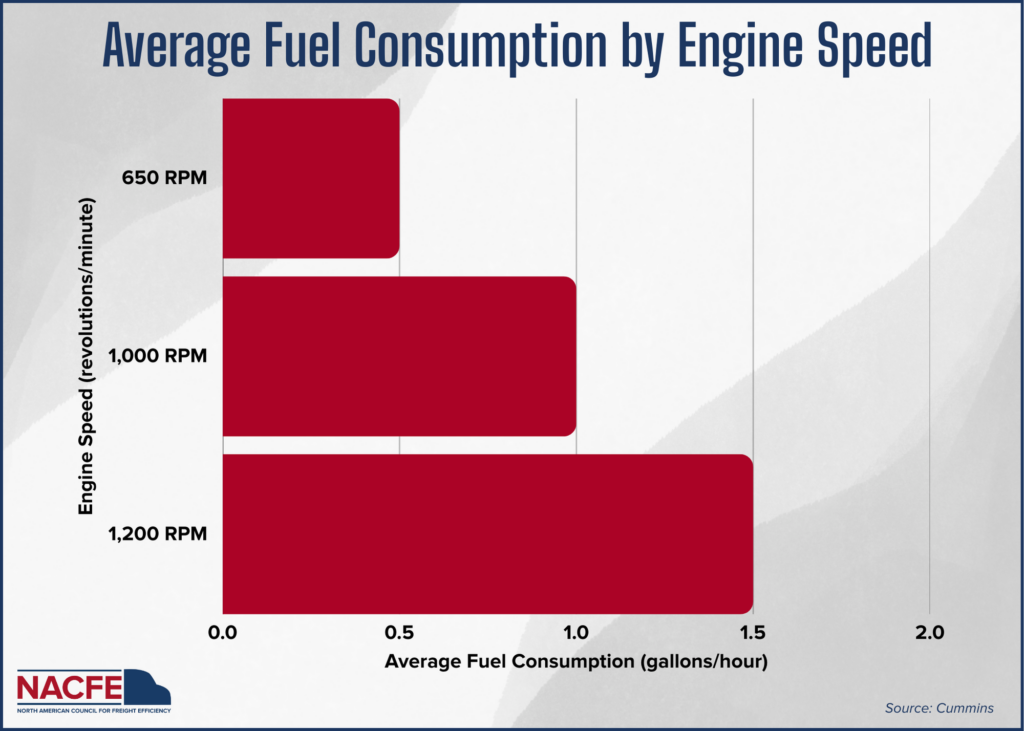

Meanwhile, diesel APUs can supply heating, cooling, and electrical power while the main engine is off, using between 0.1 and 0.5 gallons of fuel per hour depending on conditions like ambient temperature, the sleeper’s insulation, the resulting HVAC load, and the generated AC power.

Generally, a modern diesel APU burns roughly 75% less fuel than an idling tractor engine, saving up to about 2,500 gallons of diesel per truck per year, or approximately 10,000 gallons over a four-year trade cycle.

While they can significantly reduce engine idling and extend engine life, NACFE says that their higher upfront cost, maintenance requirements (APU’s engine needs oil, filters, and valve adjustments every 500 to 2,000 operating hours) and added weight of 400 to 500 lbs to the weight of the truck can lengthen payback periods.

Electric APUs (eAPUs) offer potentially significant fuel savings, with NACFE estimating typical reductions of 1,200 to 1,800 gallons of diesel per truck annually — and up to 2,500 gallons in some long-haul applications. Because they operate with the main engine off, eAPUs produce zero tailpipe emissions during rest periods and reduce engine wear and aftertreatment maintenance demands. When paired with solar panels or shore power, modern battery-based systems can support hotel loads for a full rest break, and at diesel prices of around $4 per gallon, fleets can achieve payback in 18 to 30 months.

However, diesel APUs are more common than eAPUs due to their predictable performance and established service network. While, diesel APUs offer virtually unlimited runtime as long as fuel is available and can handle both heating and cooling through a single system, many eAPUs struggle to provide a full 10-hour rest period of cooling in extreme heat and typically still require a separate diesel-fired bunk heater in winter. The can also add about 345 to 400 lbs. to the tractor weight.

Fleet managers also cite concerns around battery replacement costs, as AGM-based systems often require battery change-outs every 24 to 36 months, while longer-lasting lithium packs increase upfront costs to roughly $9,000 to $16,000 per tractor. NACFE notes that despite favorable payback windows, sticker shock remains the biggest barrier to broader eAPU adoption.

Fuel-operated heaters

Commonly paired with eAPUs are fuel-operated heaters, using diesel-fired heat in winter to preserve battery capacity for summer cooling. NACFE says these heaters are among the most mature and widely adopted idle-reduction technologies and generally fall into two categories: fuel-operated air (bunk) heaters, which warm the sleeper directly, and fuel-operated coolant heaters, which circulate heated antifreeze through the engine block to maintain its warmth.

According to the report, the devices are relatively inexpensive, reaching up to $2000 per installation and provide a quick payback in fuel savings, with some carriers seeing payback in well under a year. While fleets in cold climates frequently make bunk heaters standard equipment, all major OEMs offer fuel-fired heaters as a factory option, too, which can be retrofitted in the aftermarket.

Intelligent Engine Management Systems

More advanced idle-reduction gains are increasingly coming from intelligent engine management systems and thermal management technologies, which NACFE describes as a shift away from simple idle timers toward automated, data-driven decision-making.

These systems include smart shutdown or auto-start/stop systems that use vehicle data like coolant temperature, battery state of charge and sleeper cabin thermostat setting to decide when the engine actually needs to run, shutting it off when conditions allow and restarting it only when necessary.

Some of the more advanced predictive systems can analyze telematics data, such as GPS location, weather, traffic, and dispatch schedules, to determine if the engine will sit unused for several minutes, turning it off preemptively.

Neutral idle systems automatically shift an automatic transmission into neutral when a truck comes to a stop, reducing the load on the engine while it remains running.

Meanwhile, contextual idle management systems use real-time data — including GPS location, duty-cycle indicators, PTO status, weather, and local anti-idling rules — to determine why a truck is stationary. Based on that context, the system decides whether the engine should continue running, switch to an electric APU, or shut down.

And adaptive power management systems treat the truck’s batteries, alternator, hotel loads, and any eAPU as a single, integrated self-optimizing energy system. They manage charging while the truck is moving and meter power during rest periods, automatically prioritizing shore power or solar energy when available and minimizing unnecessary engine use.

Thermal management technologies – like advanced cabin-climate control and phase-change material technologies — are also helping fleets limit idling by keeping cabs comfortable with the engine off.

Idle-reduction strategies

But idle reduction extends beyond hardware and depends on a combination of passive vehicle enhancements, driver behavior, operational policies, and digital optimization, NACFE said.

Fleets can implement various measures, such as reducing HVAC demand by parking with the windshield facing away from the sun, closing sleeper curtains, or using reflective shades in hot weather. In cold weather, plugging in block heaters where available reduces the need for overnight idling.

Implementing other everyday driver practices, such as shutting engines off during short stops, limiting warm-ups in mild weather, and using bunk heaters or APUs instead of the main engine when parked, can deliver meaningful fuel savings. NACFE suggests that implementing management policies — including driver training, incentives, access to yard facilities, and hotel use when appropriate — will facilitate long-term adoption and driver buy-in.

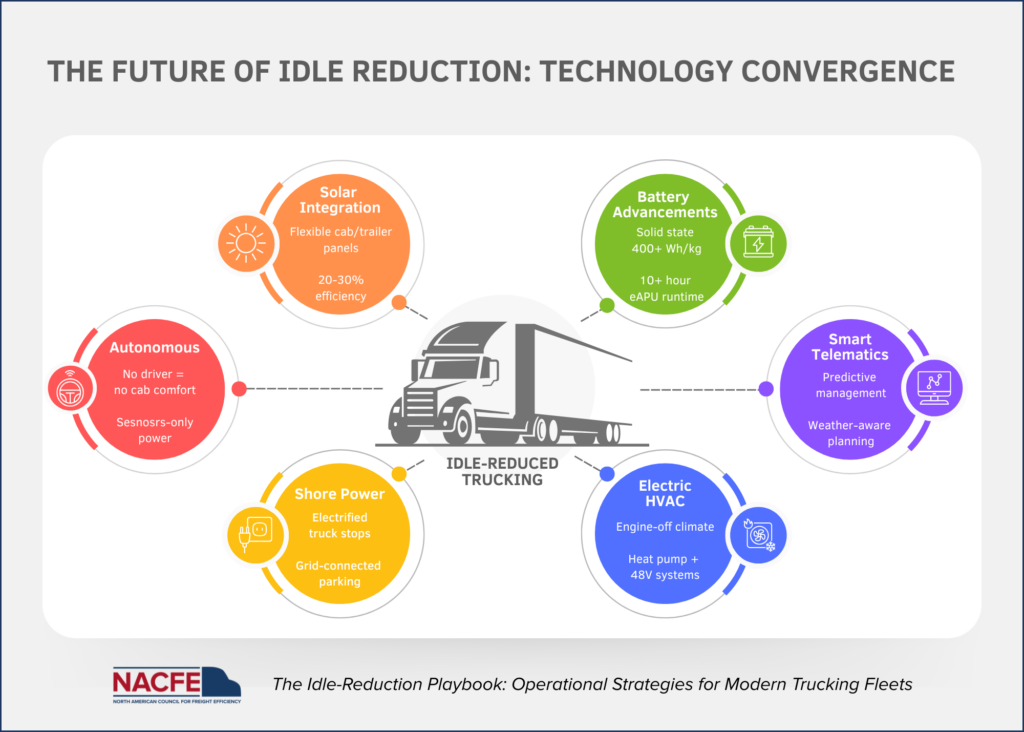

NACFE expects emerging technologies will further transform idle reduction over the next five to 10 years, as major telematics platforms are now evolving into IoT ecosystems that combine engine data, fuel flow, and cabin sensors with cloud-based analytics, enabling real-time idle monitoring and optimization.

Have your say

This is a moderated forum. Comments will no longer be published unless they are accompanied by a first and last name and a verifiable email address. (Today's Trucking will not publish or share the email address.) Profane language and content deemed to be libelous, racist, or threatening in nature will not be published under any circumstances.