What truck fleets need to know about electric vehicle batteries

If your understanding of batteries extends only as far as AAA, AA, C, and D, you have some catching up to do. Truck fleets will soon need to be familiar with terms like NMCA, LTO, LFP, and more. Those are the acronyms for some current and emerging battery technologies for automotive and truck applications.

In the early days, OEMs will be making all the battery spec’ing decisions for battery-electric trucks, but fleets will eventually be offered choices.

“OEMs and fleets are still on the up-side of the learning curve,” said Rick Mihelic, director of emerging technologies at North American Council for Freight Efficiency (NACFE) and formerly a vehicle performance engineer at Peterbilt. “The OEMs don’t have all the answers yet. It will take a few years to flesh out all the options, but I expect fleets will eventually have battery spec’ing options.”

Already, some battery chemistries are proving to be better suited to certain applications than others. Lithium-titanium-oxide (LTO) batteries, for example, can be charged quickly, but have a lower energy density (they are heavier) than other battery types. Nickle Manganese Cobalt (NMC) batteries, on the other hand, have high storage capacities and are well suited for long-range applications, but they are relatively new to the market and still in development.

“Depending on what you’re going to do with the battery, you might choose a different chemistry for different applications, even within the same fleet,” said John Warner, chief customer officer at American Battery Solutions, speaking at the annual general meeting of the American Trucking Associations’ Technology & Maintenance Council (TMC).

But the choices in battery types and chemistry go beyond the application. Warner said there are many factors to consider, including safety, weight, performance, cost, recyclability, and even form-factor and packaging possibilities.

“Number one is safety,” Warner told the audience. “If it’s not safe, nothing else matters.”

Battery fires, though relatively rare today because of the scarcity of electric vehicles on the road, are a significant concern for vehicle owners as well as emergency responders. A lithium-ion battery can burst into flames long after it was damaged, points out Raul Battista, manager of alternative power systems at Penske Truck Leasing.

“They can be exceptionally difficult to extinguish, and with the massive amounts of energy in commercial battery system(s), they can flare up again and again,” he said. “They emit combustible and harmful gases, and there’s a risk of environmental contamination due to the contaminate run-off water from fire-fighting efforts.”

Even a single cell failure within a battery pack can lead to a vehicle-level event. Batteries are subject to crash testing, just as diesel, natural gas and hydrogen storage tanks are today, but in these early days, standards for crash damage are just being written.

“I’m working on a lot of standards committees right now because they haven’t been written yet,” Warner said.

Battery safety at the standards level won’t be a fleet concern, beyond knowing the battery is certified safe. However, fleets will have to be up to speed on fire-fighting procedures for potential in-shop events, post-crash fires, and when dealing with first responders and the community at large.

Performance matters

As Mihelic noted, OEMs are still working out the details of battery performance based on intended applications. Spec’ing options are necessarily limited at the moment, but eventually you may be able to consider trade-offs in the battery spec’, such as the ability to fast charge or take advantage of regenerative charging and opportunity charging.

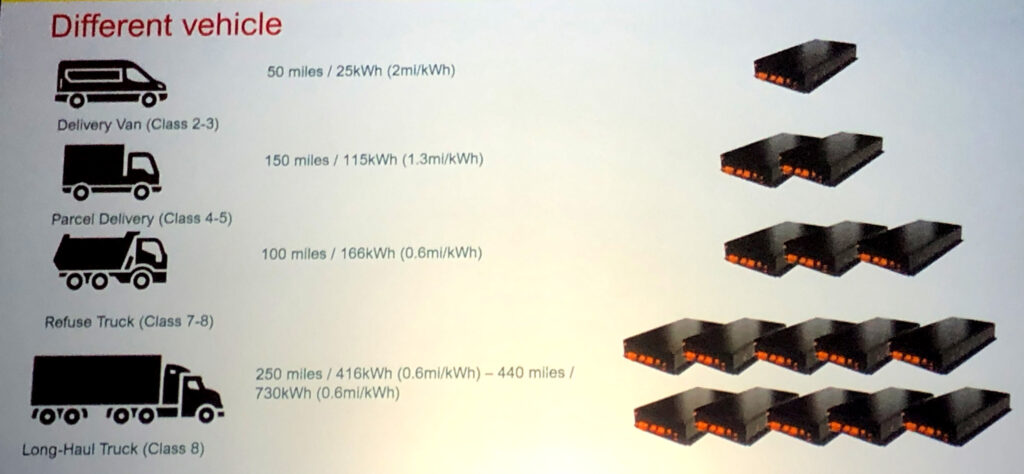

Battery size and weight are serious concerns, so optimizing the application’s battery is critical. As an example, Warner compared a package delivery vehicle with a refuse truck and a class 8 longhaul truck. He noted the package delivery vehicle would consume about 1.3 kilowatt-hours per mile. For a range of 150 miles (240 km), it would need a battery with about 115 kWh. A refuse truck, obviously heavier, would get about 0.6 miles (.97 km) per kWh. Its battery would need to be about 166 kWh to complete for a day’s work.

“As the vehicle weight increases, energy demand increases,” Warner says. “You also have to build in some contingency for hot or cold weather, and some reserve. But if you can rely on regen charging, as in a high stop-start application like refuse or package delivery, choosing a battery chemistry optimized for regen charging may let you get away with a smaller, lighter battery overall.”

When you start considering the various chemistries on the market, the pros and cons of each soon become apparent. In the short term, selection will be limited to what the OEMs are comfortable with, but fleets will need to get up to speed on the offerings and their potential benefits.

“Fleets will need to understand the parameters associated with high-voltage batteries and how they will fit into the operation,” Battista said. For example, is the battery’s lifecycle based on time, hours, miles, or energy throughput? Does DC fast charging have adverse effects on your warranty? These factors and others should be considered when deciding the application of your vehicle and its battery needs.”

Round peg, square hole

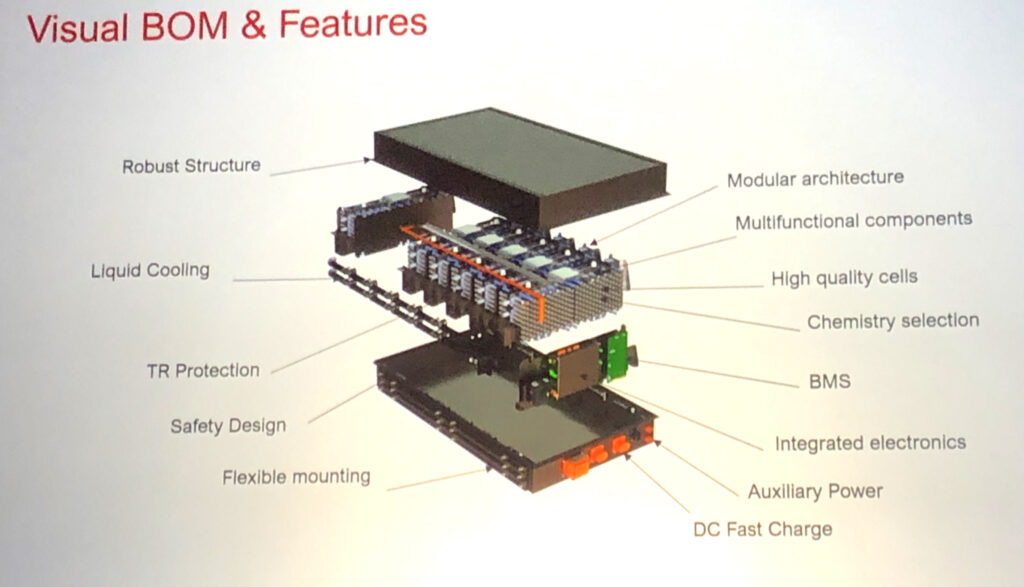

Packaging is another interesting part of the equation. The actual battery cells used in commercial EV batteries look much like a typical double-A battery. Hundreds or thousands of them are wired together and packaged into modules of standard capacities. How many modules you get depends on the capacity you’re looking for and the available space on the chassis. Weight is an additional consideration.

The shape of the individual cells is mostly cylindrical, but that’s not always the best use of the space. Other shapes are being considered, but there are other concerns, such as heat dissipation, that need to be addressed. You can stuff only so many cylindrical cells into a rectangular box. And the rectangular modules form full packs that may not always comfortably fit onto a chassis with lots of rounded corners, as with today’s aero tractors.

The type of enclosure is important, Warner stressed. “What type enclosure is it? What environment is it going into? How can we crash-proof it? Will its position on the vehicle protect it or expose it?”

These will be spec’ing concerns for fleets sensitive to wheelbase length, tare weight, and the truck configuration. Vocational vehicles may be particularly challenging, considering the weight and frame-space requirements of the onboard implements.

Part of today’s challenge is the number of systems and standards out there. The battery makers can design systems to suit any application, not just for trucks. But at some point, the need to manage manufacturing costs will force certain packaging configurations. Those require standards, and there is no shortage of standards out there, either. Warner listed five off the top of his head. And Europe and China have different standards than we do here in North America.

Future considerations

The next great hope is solid state batteries. They are a work in progress that everyone hopes will succeed. Solid-state batteries feature a solid electrolyte, unlike lithium-ion batteries that contain a liquid electrolyte. It means solid state batteries offer a greater energy density and lighter weights – in other words, more range per pound. They also recharge faster. Solid-state batteries are common in small devices such as computers and cell phones, but it’s proving difficult to scale the batteries up to the size and capacity needed for cars, nevermind commercial vehicles.

The prospect of have a better battery just beyond the horizon gives electric truck buyers jitters. Nobody wants to invest heavily in what could prove to be a marooned technology. Fortunately, according to Warner, different options are still a few years out from commercial deployment.

“I think you’ll see some automakers playing with some kind of low-volume production, probably in 2025 to 2026, but it will be more like 2030 by the time it expands out into the rest of the industry,” he said.

He noted that it will come in in phases — it won’t be pure solid-state – starting with somewhat of a hybrid with a metal anode and maybe a gel or a semi-liquid electrolyte.

Replace and recycle

Fleets will eventually be confronted with what to do with worn out or expired batteries that have diminished capacity to hold a charge. While batteries are presently an enormous part of the total cost of an electric vehicle, prices are dropping. Future replacement batteries could be lighter, more powerful, and less expensive. But fleets probably won’t get a good trade-in deal on the existing batteries because they may be obsolete by trade-in time.

Experts suggest there will be a market for the older batteries as stationary energy storage, and they could be downsized to operate in smaller devices. It’s still too far off to see clearly what uses your present batteries will come to, but fleets will eventually have to make cradle-to-grave decisions about their battery specifications.

Three’s no time like the present to start getting up to speed on EV batteries.

Have your say

This is a moderated forum. Comments will no longer be published unless they are accompanied by a first and last name and a verifiable email address. (Today's Trucking will not publish or share the email address.) Profane language and content deemed to be libelous, racist, or threatening in nature will not be published under any circumstances.