10 things we know (and a few we don’t know) about electric trucks

Several OEMs have unveiled plans to begin production on electric trucks in 2021/22, expanding beyond the limited number of units in today’s test fleets.

Before you plug in to the excitement, here are 10 things we know – and a few things we don’t know – about electric trucks.

1. The drive for electric trucks goes well beyond Tesla

Elon Musk and Tesla attracted plenty of attention in November 2017 when unveiling the prototype of a battery-electric Class 8 Tesla Semi. But it is hardly the only manufacturer with an eye on the goal of producing a viable electric truck.

Established OEMs including Daimler, Volvo, Navistar International, and Paccar already have test trucks hauling freight and plan to begin production in 2021/22. And the number of non-traditional nameplates continues to grow – including the likes of U.S.-based Nikola Motor, China-headquartered BYD, and Canada’s Lion Electric, to name a few.

Even with all these players, initial volumes will be limited in the near term. Paccar vice-president Jason Skoog recently predicted North American manufacturers would collectively produce fewer than 1,000 electric trucks per year in 2021 and 2022.

Compare those numbers to the size of the marketplace. According to WardsAuto, Canada and the U.S. accounted for more than 215,500 Class 8 truck sales in 2020 alone.

2. The race is also about more than trucks alone

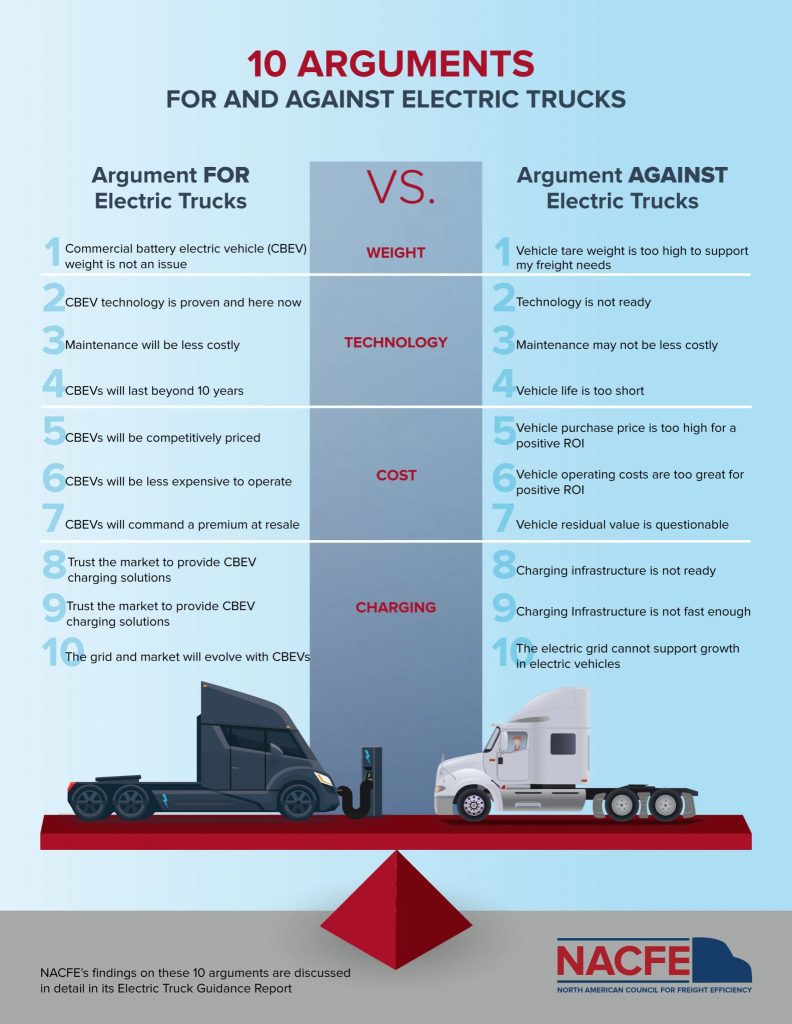

While there’s plenty of interest in battery-electric vehicles, there are still plenty of barriers to widespread commercial rollouts.

Such trucks come with a premium price tag when compared to their diesel-powered counterparts. Limited charging infrastructure will usually support no more than a handful of vehicles at a particular location. Today’s batteries have power densities that can support lighter parcel delivery vans and short routes, but fall short of what would be needed for a longhaul tractor-trailer.

That’s where test vehicles come in. Truck manufacturers are joining with their customers to refine the answers around everyday operational issues, such as where, when, and how charging is best completed.

The tests aren’t limited to the U.S. Purolator, for example, recently deployed 18-foot Ford step vans powered by Motiv Power Systems in Vancouver. SAQ, Quebec’s liquor distributor, is testing a Lion8 box truck in Montreal.

Several major Canadian fleets including the likes of Bison Transport and Loblaw have also placed orders for their first electric Class 8 trucks.

3. Favorable jurisdictions are not limited to California

Much of the early interest in battery-electric trucks is focusing on California, which will require 40% of new Class 7/8 tractors and 75% of new Class 4-8 straight trucks to be zero-emission vehicles by 2035. But some Canadian markets offer favorable settings, too.

The North American Council for Freight Efficiency (NACFE) lists the Greater Toronto Area, Greater Montreal, and the Cascadia Region stretching from Vancouver to Oregon among the most favorable regions for electric truck rollouts.

One of the reasons is that densely populated areas support shorter potential journeys between recharging opportunities. But available financial incentives also remain a key tool to help offset premium prices on the equipment and required charging infrastructure.

Quebec’s Ecocamionnage Program offers up to $175,000 per electric truck. And a recently expanded CleanBC Go Electric Commercial Vehicle Pilot Program will now cover up to $100,000 toward the cost of an electric medium- or heavy-duty vehicle.

4. Battery prices and weights are plunging, but there is still far to go

The need for financial support can be traced in part to the price of the batteries themselves. The good news is that they’re trending in the right direction.

A 100-kWh battery that cost $110,000 in 2010 is expected to be worth just over $10,000 by 2023, according to analysts at Bloomberg NEF.

The price isn’t the only thing to drop. A 100-kWh battery that weighed 1,000 kg in 2009 weighs about 2/3 as much today. By 2025, the weights are expected to drop as low as 400 kg. And there is a direct link between battery weights and the battery capacity that can be added to a truck in the name of extending range between recharging opportunities.

To put the numbers into perspective, commercial trucks will typically require 200-500 kWh of batteries to perform the work they do today.

5. The energy is clean, but it isn’t free

The cost of the electricity needed to recharge electric vehicles varies by jurisdiction, and that can also influence plans for widespread electric truck rollouts.

For example, electricity costs 12.03 cents per kilowatt-hour in Toronto, 5.64 cents in Montreal, and 7.03 cents in Vancouver, NACFE reports.

This can still lead to lower operational costs to help offset the higher upfront purchase prices, though.

NACFE says the electricity costs are still cheaper than the cost of equivalent power from a diesel engine, when considering a truck that averages 6 mpg (39.2 liters per 100 km). Such energy savings amount to 56 cents per mile (90.12 cents per km) in B.C. and Quebec, and 35 cents per mile (56.33 cents per km) in Ontario.

6. The range anxiety is real

Then there’s the anxiety around just how far the trucks will travel.

Lighter package delivery vans, refuse vehicles, and the drayage trucks that run between ports and warehouses benefit from short, predictable trips. They can return to a home base for recharging at the end of a shift. This makes them prime candidates for earlier electric vehicle adoption.

One in five trips run by Loblaw’s fleet, for example, venture no further than 100 km from a distribution center, according to senior director – transport maintenance Wayne Scott. Grocers also work with diminishing loads, which could add to the potential range and support most DC-to-store deliveries.

Battery-electric trucks to roll out over the next three years are predicted by NACFE to offer an average range of 460 km between charges. Given that few users would drain the batteries until they’re completely empty, the practical range is closer to 370 km when keeping everything above a 20% state of charge.

That still isn’t enough for some operations. A longhaul truck driver will typically travel more than double that distance in a given shift.

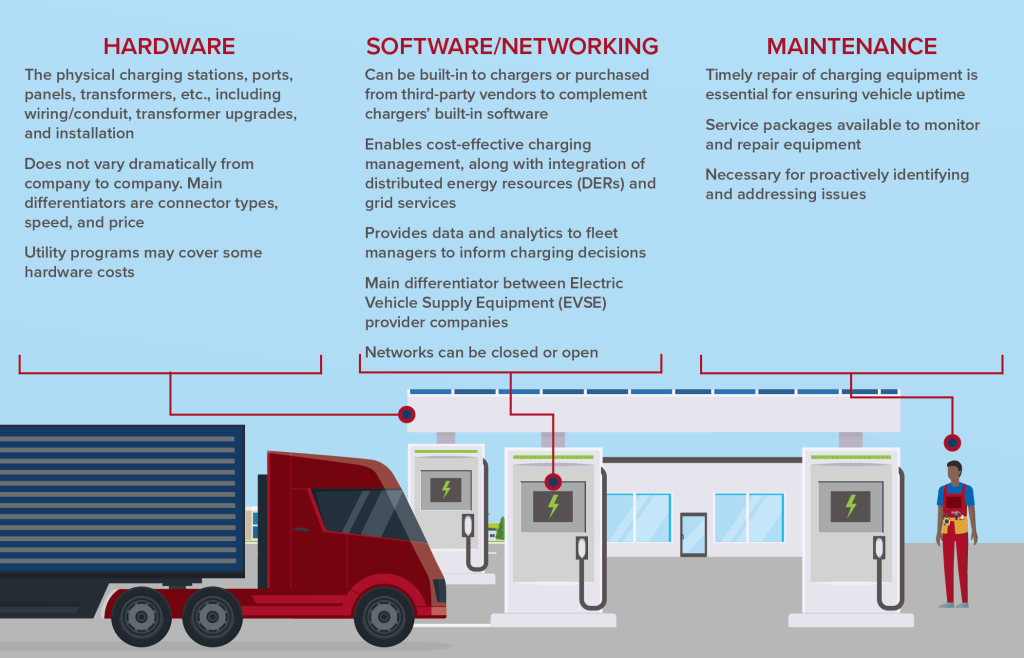

7. Commercial vehicle chargers require more than a standard household outlet

As important as the range between charging stations will be, the charging time also plays a role in productivity. And there’s a significant difference between a widespread electric vehicle rollout and a fleet that simply repurposes a welder’s power source to recharge a single test truck.

Aside from the required infrastructure upgrades, charging times need to align with factors like Hours of Service limitations, and energy costs that can vary by time of day. Underlying software and vehicle telematics platforms will be needed to find the balance.

Then there’s the challenge of building the infrastructure in the first place. Scott noted during an earlier interview that a fully electric Loblaw fleet could require a sixfold increase in the power used by a typical distribution center today. The options vary by location, too. At one site, Hydro Quebec was able to locate high-voltage power lines nearby, and the lot had a 600 kV transformer that was only 40-45% utilized. Other locations would require significantly larger infrastructure investments.

Recharging times are another matter altogether. It isn’t always practical to have a truck sitting still for hours as it waits for power.

In the search for quicker charging speeds, CharIN (Charging Interface Initiative) is looking to develop High-Power Charging for Commercial Vehicles standards that would make it possible to recharge Class 6, 7 and 8 trucks in less than 30 minutes.

But these are no ordinary extension cords. Such chargers would require upgrades such as liquid-cooled cables, and dedicated connectors that can deliver 1,500 volts/3,000 amps.

Let’s put it another way. A Nissan Leaf can charge overnight using a standard 120-volt outlet. The charging time cuts in half if the household garage has a 240-volt/80-amp outlet. A CCS DC fast charger will bring a 100-kWh battery up to an 80% charge in about 20 minutes. That will require about 1,000 volts/500 amps and draw 250-500 kW of power.

8. Don’t forget the maintenance upgrades

Electric truck producers are quick to point out potential maintenance gains. There won’t be any work on internal combustion engines (goodbye in-frame overhauls), and brakes will also last longer when regenerative braking is used to extend vehicle range.

There will be some unique maintenance considerations, though. The trucks themselves will require larger cooling systems to maintain battery conditions. Shops will also need to gain experience in the related electric motors and e-axles, in addition to the charging systems themselves.

There will even be changes in the maintenance shops and procedures to consider. Tools will need to be insulated, and PPE will include insulated gloves, shock jackets, and arc shields. Health and safety considerations will require training in high-voltage systems.

9. Canada will produce commercial electric vehicles

Some of North America’s early battery-electric commercial vehicles will roll off Canadian assembly lines.

General Motors will build BrightDrop electric light commercial vehicles at its CAMI manufacturing plant in Ingersoll, Ont., part of a $1-billion investment to bring the BrightDrop EV600 to market in late 2021.

Lion Electric, meanwhile, is now taking orders for its Class 8 trucks to be produced in Quebec. It’s also committed to building a battery manufacturing plant and innovation center in the province.

The work is not limited to truck OEMs, either. Dana now holds a majority stake in Quebec’s TM4, which produces the all-important motors and inverters for electric vehicles.

10. It’s not all about batteries

While there has been plenty of attention around battery-electric vehicles, those running heavier weights and longer distances are exploring fuel-cell-electric vehicles.

These trucks will draw on tanks of hydrogen to generate the required energy.

Canada’s federal government recently committed $1.5 billion to help build a hydrogen economy, and is promising the refueling infrastructure to support 5 million fuel cell electric vehicles by 2050.

Some of the same truck OEMs interested in battery-electric vehicles are also looking at fuel cells.

Daimler and Volvo have formed a joint venture to develop a system capable of delivering 300 kw of continuous power – enough to support a commercial truck. Nikola Motor, which struggled to produce a system of its own, says it will now integrate GM’s Hydrotec fuel cell into Class 7 and 8 trucks, with prototypes coming this year. Toyota and Kenworth are testing fuel cell vehicles in California. Navistar is joining with General Motors and OneH2 to roll out trucks and a refueling network combined.

Similar trucks will soon be on Alberta highways. Trimac Transportation and Bison Transport are scheduled to participate in the Alberta Zero Emissions Truck Electrification Collaboration between this October and April 2023.

Have your say

This is a moderated forum. Comments will no longer be published unless they are accompanied by a first and last name and a verifiable email address. (Today's Trucking will not publish or share the email address.) Profane language and content deemed to be libelous, racist, or threatening in nature will not be published under any circumstances.