Mob Rule: Italian mafia leading source of cargo theft

NIAGARA FALLS, Ont. – Todd Moore was playing hockey in Hamilton, Ont., when some guys came forward with 10 cases of Moosehead beer that had “fallen off a truck”. He knew exactly where it had come from, though. Everyone knew. The theft of two loads of beer in New Brunswick had been all over the news, complete with jokes about Moose being on the loose.

It was no joke to the career police officer, now president of Canadian Armed Robbery Training Associates.

All too many people turn a blind eye to the cost of cargo thefts, he said during a presentation to the Private Motor Truck Council of Canada. Contractors might see a cheap load of lumber as a way to cut costs, just like a chef who’s offered a deal on a load of beef that’s too good to be true. “People don’t see the significance. They say it’s ‘insurance’,” he admitted. “But everybody is paying.”

The Greater Toronto Area now has the highest rate of cargo theft in Canada, rivaling major U.S. centers. Research by the Canadian Trucking Alliance and insurers suggests the crime across Canada costs about $5 billion a year.

A typical cargo theft is now valued at about $196,000, with more than $500,000 in goods disappearing every day in the Toronto area alone. That rivals numbers seen in crime capitals like Los Angeles, Dallas and Miami. In the first quarter of 2017, Ontario actually displaced Texas as the Number 2 jurisdiction for cargo thefts in North America, representing $4.3 million in missing products.

Drug cartels fueled cargo crime in Mexico, where 3,300 such thefts were recorded in a single quarter this year, and they’re also behind many of the gang-related thefts in the U.S. But in Canada, Moore says traditional organized crime groups are at the top of the food chain.

Mafia connections

In the Greater Toronto Area and Montreal, the leading mafia groups include the ‘Ndrangheta, Cosa Nostra, and Camorra, which can be traced to Italy and Sicily. The Cosa Nostra is likely the most widely known. “They’ve been involved in cargo thefts and hijackings for decades,” Moore says. But the ‘Ndrangheta mafia – otherwise known as the Calabrian Mafia — is the biggest in the GTA and the world at large. It has 10 related groups in the GTA and Hamilton, Ont. alone.

The Calabrian mafia’s 25,000 made members with 250,000 affiliates and associates made an estimated $75 billion in 2017 alone. He calls them the “McDonald’s Mafia” because of it.

In Montreal, the Sicilian Mafia connected to the original “five families” of New York City has a stronger presence, although it also has an active cell in the GTA.

They don’t work alone, either. The mafia groups also work alongside outlaw motorcycle gangs, and organized crime cells linked to Russia and Europe.

“It’s set up like a normal business,” Moore says.

A cargo theft network might include a warehouse used by thieves to store stolen loads and distribute contents to buyers. Other members target specific loads, often for pre-arranged buyers. Yet other members target random loads as crimes of opportunity, while stolen food is unloaded in restaurants connected to organized crime. Then a broker or “fence” receives a stolen load and distributes it to prospective buyers, paying a commission to the mafia.

It’s often an inside job, too. “Someone who’s vulnerable, and someone who might be in trouble,” Moore explained. Inside information could come from truck drivers who are slipped $5,000, or maybe warehouse supervisors, or shippers and receivers themselves. Thieves might choose to extort or intimidate a driver who has gambled away $10,000, a debt that can double every three weeks in an illegal gaming house. In other cases, they might threaten to expose incriminating information.

The targets

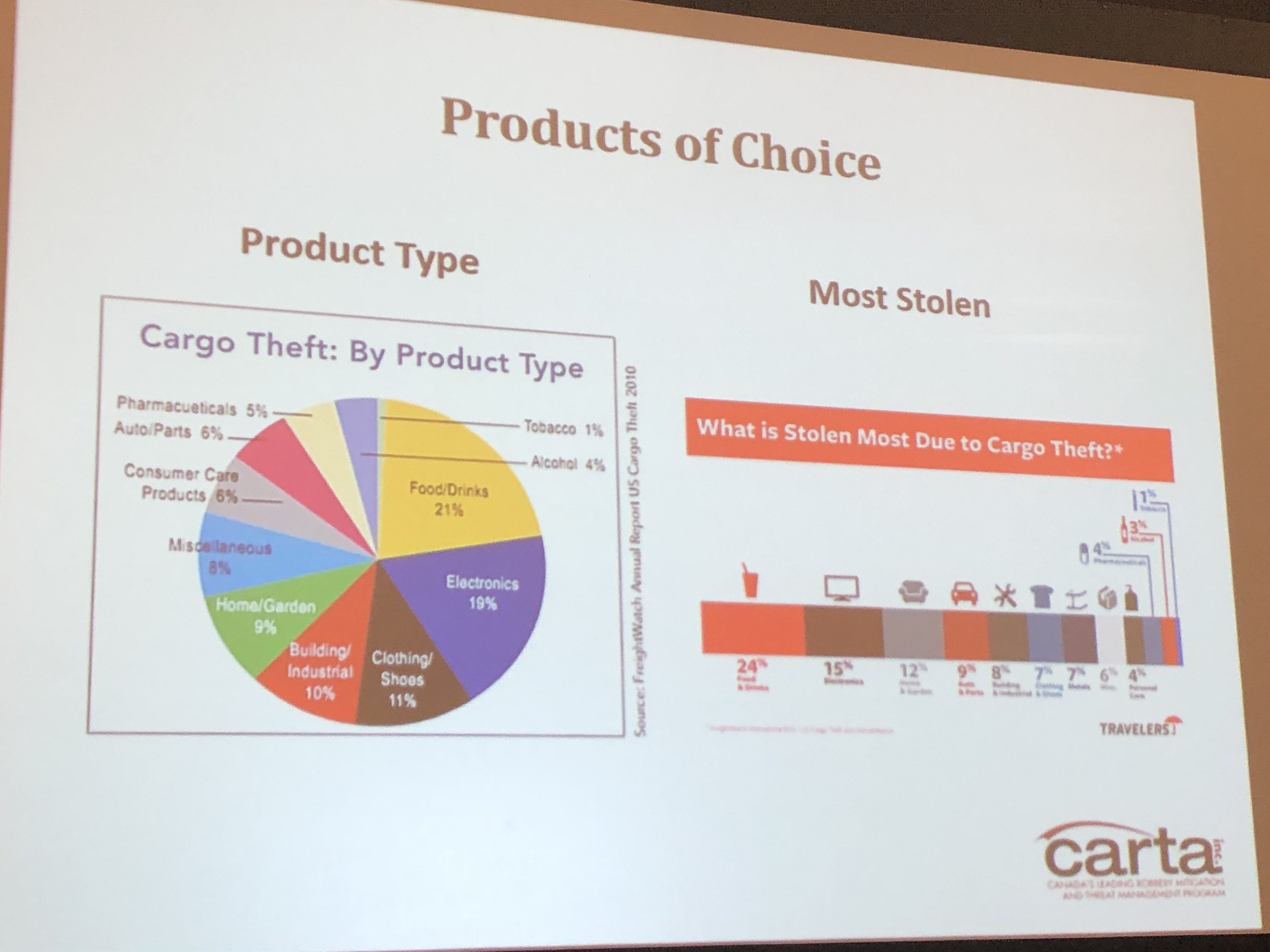

Nothing seems to be safe. Travelers Insurance has cited FreightWatch statistics showing that 24% of cargo thefts involve food and drinks, followed by electronics (15%), home and garden products (12%), and autos and parts (9%). “There’s an underground market for anything,” Moore said.

But it’s important to realize that the thefts are not ends unto themselves. Usually they help to finance other crimes such as dealing drugs. The $196,000 in goods stolen in an average heist, for example, could pay for 128 kg of cocaine with the potential of a 10-fold profit, he explained.

It also offers the promise of low risk and high reward.

In 2015, an average bank robbery netted $4,330, with a retail robbery averaging $1,589 and convenience store robbery averaging $769. If a thief uses a firearm during such a crime they face a minimum of four years in prison. With a pellet gun they face at least a year behind bars. “With cargo theft you don’t have any of those minimum sentences,” Moore said.

Admittedly, there are more tools than the past. The relatively new Auto Theft and Property Crime Act offers a maximum term of 14 years for trafficking or possessing stolen property. But that’s the law as it’s written. “I guarantee no one is getting 14 years,” Moore said.

To compound matters, police have few resources to stop it.

“In policing we have strategic plans, we have investigations that are prioritized,” Moore told the crowd of fleet managers. “Some things get attention and some things don’t.”

The Greater Toronto Area includes three major organized crime units – the Combined Forcers Special Enforcement Unit, the RCMP Toronto Airport Serious and Organized Crime Unit, and OPP Biker Enforcement Unit, but there is ongoing competition for resources. Since 80% of Canada’s 670 organized crime groups are involved in drug trafficking, that gets the focus.

“We have budget restrictions and investigative priorities and every interest group thinks their investigation is most important,” Moore said. The irony is that cargo thefts often provide the seed money for many other criminal activities.

In contrast, there are only seven dedicated cargo theft teams in the U.S., in California, Texas, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Tennessee, and N.Y. The only such units in Canada are in the Toronto area’s Peel and York Regions. But since they aren’t Tier 1 investigations, there’s no funding for wiretaps or running agents, Moore says.

Cargo theft units are instead left with tools like tips through Crime Stoppers, confidential sources, surveillance, and canvassing property owners for security video. But with six officers responsible for hundreds of thefts, only so much can be done. “There’s so much volume it’s hard to focus on your particular cargo theft,” he said.

Besides, three in four cargo thefts aren’t even reported, Moore said. “There’s probably very good reasons.” Fleets might worry about how a report might affect insurance costs, or their reputation with other potential customers.

Finding the stolen property doesn’t always solve the problem, either. Moore referred to the theft of 15,000 kg of candy from a rented parking lot in York Region. The $200,000 in goods were recovered, and two people were arrested, but the foodstuffs had to be sent to landfill because there was no way to track the chain of custody. “Even when an arrest is made, even a success can be a failure.”

The tools

Fleets are not completely powerless when it comes to battling cargo crime. Guards at access gates can verify the identities of drivers and carriers, while human resources teams can conduct employee background checks. One of Moore’s police sources said almost half his information came from inside employees. “You want to weed these people out before they ever become employees.”

Another key tool has come in the form of a central database, the CTA Cargo Crime Incident Report, established in 2014 by the Canadian Trucking Alliance and Insurance Bureau of Canada. With that, it’s possible to identify what is stolen and where.

Technology offers help of its own.

“The Number 1 thing is to GPS the trailer,” Moore said of the tools he recommends. A “slap and track” device will activate if a trailer begins to move, and when configured with a personal device for the driver it can offer instant tracking information. Fleet teams could then trace stolen goods to a warehouse and give police the data needed to secure a search warrant.

Covert police teams often use cellphone-based cameras, he added. They don’t require an internet connection, and can be fixed inside the trailer, storing images on a SIM card. Infrared systems will even capture views in the dark.

A portable intruder spray, meanwhile, can be magnetically attached to a trailer, leaving a forensic marker on property and bad guys alike if someone breaches the barn doors. The spray is invisible to the naked eye but seen under UV light. Police can be provided with the equipment to read it. Fleets can use its presence as a deterrent, by posting stickers and signs that warn of the system in place.

Still, one of the keys is to convince the public that this is not a victimless crime, he said. “You have to somehow change the mindset of the general public to realize this is an epidemic.”

“It is a huge problem,” Moore said. “But it is a fixable problem.”

- An earlier version of this story has been edited to correct Todd Moore’s name. Today’s Trucking regrets the error.

Have your say

This is a moderated forum. Comments will no longer be published unless they are accompanied by a first and last name and a verifiable email address. (Today's Trucking will not publish or share the email address.) Profane language and content deemed to be libelous, racist, or threatening in nature will not be published under any circumstances.